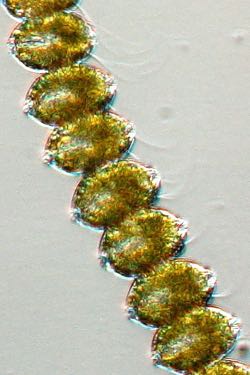

Alexandrium monilatum

Scientific Name

Alexandrium monilatum

Distribution

Alexandrium monilatum is a common HAB (harmful algal bloom) species that historically blooms along the southern Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the U.S., with a recent expansion into the mid-Atlantic region and Chesapeake Bay. A. monilatum was first conclusively detected in Chesapeake Bay in 2007, when researchers at VIMS used microscopy and DNA sequences to identify it as the dominant species of a bloom that persisted for several weeks in the York River. Blooms of A. monilatum are prevalent in Chesapeake Bay in the late summer months, usually July-September, and have re-occurred almost annually since their emergence in 2007. In lower Chesapeake Bay A. monilatum is typically found at moderate salinities of between 20-27 parts per thousand when  water temperatures are above 25°C (77°F).

water temperatures are above 25°C (77°F).

Toxicity

A. monilatum has been associated with mortality of marine finfish and invertebrates in Texas, Mississippi Bay, Florida, and Alabama and more recent mortality of oysters and oyster larvae in Chesapeake Bay. Additionally, cownose rays and Rapana whelk held in tanks at VIMS, receiving York River water, all died during A. monilatum blooms in 2007 and 2008. The primary toxin of this HAB is the lipophilic, secondary metabolite called goniodomin A (GDA). The toxin’s potential impacts to marine life and human health remain largely unknown.

Ecology

A thecated (i.e. “armored”), chain-forming dinoflagellate that possesses single-cell, chain, and cyst life stages, using sexual and asexual reproduction, which relies on autotrophy. This phototroph can form long chains of 2-80 cells and can be the cause of magnificent bioluminescence “glowing waters” during blooms.

The recent intensification of A. monilatum activity in Chesapeake Bay is cause for concern due to its potentially important ecological and economic impacts. With the shellfish aquaculture industry in the Chesapeake Bay region rapidly expanding (now worth over $45 million to Virginia alone), it is critical that we understand the risk posed to the health of marine organisms, as well as to humans through consumption of shellfish exposed to A. monilatum.

Role in VIMS Research

VIMS researchers are studying the impact of Alexandrium monilatum on marine life, particularly larval fish and oysters, through laboratory bioassays and sentinel field studies (e.g., deployment of naïve oysters). Efforts are on-going to understand factors that drive bloom dynamics on a temporal and spatial scale, and the use of remote sensing as a method to monitor and forecast bloom development. Current research is also focused on determining the distribution of cysts (seeds) in Chesapeake Bay sediments, the accumulation and distribution of the toxin in Chesapeake marine life, and the effects of A. monilatum on the ecology of the Bay’s food web.