A Big Dumbo

R/V Henry B. Bigelow

Latitude 53.17 N, Longitude 36.07 W

After all of our success at midwater trawling, the bottom trawling is somewhat frustrating. Of course, it is not surprising that we are having more trouble with the bottom work; we are, after all, trying to pull a big net with its associated gear through a mountain chain without being able to see where all that stuff is. Added to that are the problems with weather that we have had to ride out lately. So we were all delighted when we were successful in bottom trawling at a deep station yesterday.

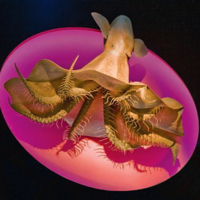

Among the catch were lots of ugly fishes, red crustaceans, and assorted other creatures. There were also several cirrate, or finned, octopods, including a very large specimen of a rarely caught species.

The cirrates were given the common name “dumbos” by research-submersible pilots because these octopods swim by flapping a pair of large ear-like fins on the sides of their bodies. This makes them look a lot like the large-eared flying elephant in the classic cartoon. Unlike the better-known shallow-water octopuses, which are muscular and don’t have fins, these octopods have a consistency similar to that of a jellyfish and they are easily damaged when caught in a net.

The cirrates were given the common name “dumbos” by research-submersible pilots because these octopods swim by flapping a pair of large ear-like fins on the sides of their bodies. This makes them look a lot like the large-eared flying elephant in the classic cartoon. Unlike the better-known shallow-water octopuses, which are muscular and don’t have fins, these octopods have a consistency similar to that of a jellyfish and they are easily damaged when caught in a net.

We have done well at sampling cirrates so far on this cruise, getting several species and some in very good condition.

Yesterday when the trawl was being hauled aboard, I could tell that there was a large octopod in it because there were numerous detached suckers stuck to the twine of the net’s webbing. When the cod-end was opened on deck the big dumbo was in there, tangled up with all of the other stuff in the catch. I pulled it free and realized that it was large indeed. Although the arms were all damaged, it would have stretched from about the height of my shoulders to the deck. It was also heavy for such a gelatinous creature, weighing about 13 lbs.

I had a guess about what species it was. The largest known dumbo species is Cirrothauma magna. Although described in 1885, it is only known from a very few specimens and none as large as this one. The standard measurement for an octopod is mantle length, which is the distance from the rounded end of the body to a point between the eyes. The mantle length on this one was about 260 mm (~10 inches). The next largest that has been reported in the scientific literature was 220 mm (~8.5 in.) mantle length. They may get much larger, though. A cirrate photographed many years ago from the submersible Alvin was estimated to be well over 6 feet in total length.

We had caught a very small specimen of this species in this area during the 2004 cruise of the Norwegian Research Vessel G.O. Sars. I had actually misidentified it at the time. Fortunately I had taken a tissue sample for DNA analysis by a colleague, Annie Lindgren. When the DNA “barcode” indicated the error, I retrieved the specimen from the Bergen Museum and dissected it for a more careful identification. I therefore felt it necessary to dissect the big dumbo to be certain of what it is. The fins of a cirrate octopod attach to a cartilaginous shell inside the bod, and the shape of that shell is very important for confident identification of a species. This shell is identical to that of a C. magna.

We had caught a very small specimen of this species in this area during the 2004 cruise of the Norwegian Research Vessel G.O. Sars. I had actually misidentified it at the time. Fortunately I had taken a tissue sample for DNA analysis by a colleague, Annie Lindgren. When the DNA “barcode” indicated the error, I retrieved the specimen from the Bergen Museum and dissected it for a more careful identification. I therefore felt it necessary to dissect the big dumbo to be certain of what it is. The fins of a cirrate octopod attach to a cartilaginous shell inside the bod, and the shape of that shell is very important for confident identification of a species. This shell is identical to that of a C. magna.

Some dumbo species sit on the bottom and then get up and swim occasionally whereas other spend all of their time drifting and swimming up in the water above the bottom. The latter is the lifestyle of our big dumbo species. They probably feed on small shrimp-like crustaceans but we don’t know much about how they catch them. It is likely that it somehow involved the finger-like cirri along the sides of the arms, from which the cirrate group gets its name. Nor do we know how long they live or much in general about their biology.

Our specimen was pretty mashed up from being in the trawl net. If you would like a better idea of what this animal looked like when it was alive, visit the Sant Ocean Hall at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History. There you can see a full-size model of a Cirrothauma magna swimming overhead, as it would appear if you could see one by standing at the bottom of the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (where we are exploring now).