SAV program monitors and restores bay grasses

A healthy Bay is a grassy Bay

The Chesapeake Bay Agreement, a legal accord among Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and the federal government, sets the goals and blueprint for Bay restoration.

VIMS’ Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) program plays a key role in measuring progress toward those goals, using aerial surveys and field studies to monitor the distribution and abundance of underwater grasses both in Virginia and Maryland. Program scientists also spearhead efforts to restore underwater grasses through planting of seeds and shoots. The group provides interactive maps and data concerning their annual surveys via their SAV website.

Program director Chris Patrick says underwater grasses are used as a barometer of Bay health because their growth depends so much on clear, sunlit water. “They’re a ‘canary in the coal mine’ for the Bay,” says Dr. Robert "JJ" Orth, who founded VIMS' SAV program in 1979.

Healthy grass beds in turn provide refuge and food for many Bay organisms, including juvenile blue crabs and young striped bass. They also provide great habitat for the recreationally important speckled trout.

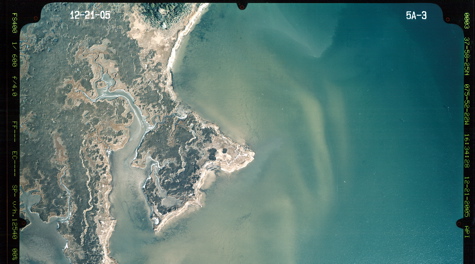

Baywide monitoring of year-to-year changes in SAV is no easy task. Each year, scientists in the SAV program at VIMS collaborate with colleagues in Maryland, federal agencies, and private business to collect aerial photographs of SAV habitat along 181 flight lines stretching nearly 2,500 miles. Ensuring good photos requires consideration of tidal stage, sun angle, air quality, water clarity, waves, and numerous other factors.

Program staff then must process and interpret these photos, an exacting and time-consuming procedure that ultimately results in a GIS database containing thousands of digital photos that reveal patches of SAV as small as one square meter. That database now includes photos reaching back to the first aerial survey in 1984.

Program staff also spends considerable time on and in the water, working with colleagues and citizen volunteers to map SAV. “We can’t tell what species are present from the air,” says Orth. “Field observations provide ground-truthing that complements our aerial coverage.” The program’s interactive website allows participants to share their field observations with others around the Bay.

“Our survey and field work are key tools for evaluating progress towards the baywide restoration goal of 185,000 acres,” says Orth. “Progress towards these long-term goals can only be evaluated in the context of year-to-year changes in the distribution and density of various seagrass species.”

Orth, who established the SAV program in 1978, still marvels at the ability of seagrasses to live completely immersed in saltwater, a condition that would quickly kill the land plants from which they evolved. Marine conditions are so difficult for flowering plants that only 60 species inhabit the sea, compared to more than 250,000 species on land.

The limited diversity of seagrasses is one reason Orth is so concerned about recent eelgrass declines in the lower Bay. “The loss of even one species represents a significant decline in seagrass diversity,” he says. Orth also laments the potential loss of the “ecosystem services” that seagrasses provide.

Orth also works collaboratively with VIMS colleague Dr. Ken Moore, who is responsible for monitoring water quality in the shallow water areas that SAV prefers. These data are crucial to understanding the changes in SAV populations documented by VIMS’ aerial surveys.

One bright spot for seagrass is the SAV program’s recent success at restoring eelgrass in the seaside bays of Virginia’s Eastern Shore, which had completely lost their eelgrass in the 1930s. During the last 7 years, with significant funding from the Virginia Coastal Zone Management/Seaside Heritage Program (CZM/VSHP), VIMS staff have broadcast tens of millions of eelgrass seeds across hundreds of acres in 3 coastal bays. As of 2020, those plantings have expanded through natural re-seeding into more than 7,000 acres of lush eelgrass meadow. In fact, they now hold 75% of the world’s restored seagrass acreage.

VIMS has partnered with a large number of organizations to make this happen, including the Campbell Foundation, the Nature Conservancy, Norfolk Southern Foundation, NOAA, Virginia CZM/VSHP, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Virginia Marine Resources Commission, the Norfolk Foundation, the University of Virginia’s Long Term Ecological Research Program, and local community volunteers.

“Our success on the Eastern Shore shows that underwater grasses can rebound quickly in areas with better water quality,” says Orth. “That’s one more reason we need to redouble our efforts to clean up the Bay.”