Middle Peninsula marshes and living shorelines create benefits valued at $6.4 million annually

It turns out that a sustainable approach to shoreline management not only has important ecological benefits for plants and wildlife, it also has a significant economic impact. Marshes and living shorelines in the Middle Peninsula region of Virginia generate more than $6.4 million in economic value from recreational fishing, a figure more than three and a half times greater than the value associated with hardened shorelines, according to a study by researchers at William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS).

Recently published in the journal Ocean & Coastal Management, the study is the first to assign an economic value to an ecological benefit of living shorelines. It highlights the unique and interdisciplinary team assembled at VIMS.

“We don’t have good models for comparing what we are losing in terms of ecosystem services when making decisions about coastal land use,” said VIMS Professor Andrew Scheld, lead author on the study and a trained economist specializing in fisheries. “That was our motivation for this work. We wanted information about the habitat preferences of anglers, and it just didn’t exist.”

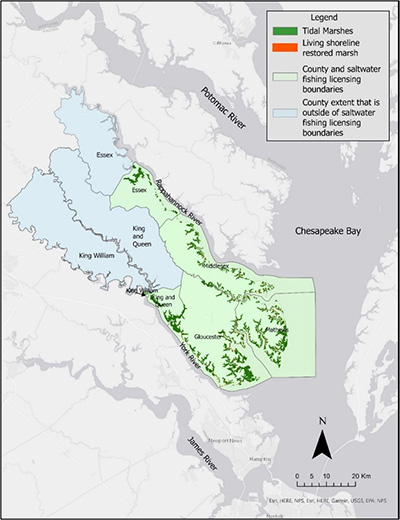

With funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and assistance from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, the researchers surveyed more than 1,500 anglers from the Middle Peninsula region of Virginia. Respondents were randomly sampled from a 2021 list of saltwater angling license holders and asked a series of questions about their fishing trips and shoreline habitat preferences.

With funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and assistance from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, the researchers surveyed more than 1,500 anglers from the Middle Peninsula region of Virginia. Respondents were randomly sampled from a 2021 list of saltwater angling license holders and asked a series of questions about their fishing trips and shoreline habitat preferences.

The data showed a clear proclivity for coastal marshes and living shorelines among the anglers due to frequent use and high willingness to pay. The researchers also estimated the total costs of fishing trips based on reported individual trip expenses plus the assessed value of the travel time for the trip. Trips to marshes and living shorelines were found to be the least expensive and require the shortest travel times across different habitats, creating substantial value for Middle Peninsula anglers.

The survey instrument was informed by a small focus group of anglers. One of them was Carl Stover, who has been fishing the Chesapeake Bay for nearly 30 years and is a volunteer tagger and instructor for the Virginia Game Fish Tagging Program, a collaborative research project among anglers, VIMS, and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission.

Stover has tagged approximately 9,000 fishes and knows the local fishing scene well. His observations are in line with the results of the study, though he thinks there are other factors that should be considered by property owners and policy makers when it comes to recreational fishing.

“The biggest thing is accessibility. People like to fish from the shore. Not everyone has a boat, and some people are fishing for sustenance and not just recreation,” said Stover. “This can make popular fishing spots like piers crowded, and it’s often not safe to fish from rocky, engineered shorelines. However, a lot of living shoreline areas are restricted to protect the environment, so the folks fishing from shore don’t have many options.”

“With living shorelines, you’re essentially creating a marsh for the purpose of protecting the shore,” said coauthor Donna Marie Bilkovic. Bilkovic is a marine ecologist and professor at VIMS whose research informs the restoration and conservation of shoreline habitats. “You hear a lot of anecdotal evidence from fishermen and property owners about increases in fish populations resulting from living shoreline projects, and this was reflected remarkably in the results of our survey.”

VIMS Marine Recreation Specialist Susanna Musick is another member of the research team. She is the principal investigator for the Virginia Game Fish Tagging Program and works closely with anglers. Being well connected to the local fishing community, she is heartened to see the research findings aligning with the observations of her fellow anglers.

“Through our tag return data, we know the importance of natural shoreline areas, especially for species like speckled trout,” said Susanna. “But, as someone who grew up fishing on the Middle Peninsula, I also know which areas offer productive shoreline habitat. It was so gratifying to see the outcomes of the study reflect the experience of the angling community as a whole.”

The action of waves against hardened shorelines creates deeper pockets of water that are less conducive to the life cycles and diets of many species of marine life. In contrast, living shorelines and marshes provide cover for smaller fish and other species important to the food chain. This creates a more diverse and resilient ecosystem, which benefits recreational fishing.

"I’ve been fishing in this area long enough to see changes in the different fisheries and the effects of different management strategies. With armor, the larger predators, like the porpoises, start to dominate because the water is deeper by the shore,” said Stover. “When fisheries disappear, so do the fisherman who put money back into the local bait shops and businesses.”

Translating ecological impact beyond recreational fishing

All 21 US coastal states have policies that encourage, endorse or require living shorelines where suitable for erosion control, and 14 have formal regulations or statutes in place. Three states – Virginia, Maryland and New Jersey – have mandates.

Last year, Virginia’s Middle Peninsula was named NOAA’s newest Habitat Focus Area. Habitat Focus Areas are designated places where NOAA focuses its programs and investments to address a high priority habitat issue through collaborations with partner organizations and communities. The Middle Peninsula was selected because it faces significant challenges from sea level rise but has the potential to become more economically and ecologically resilient through nature-based infrastructure efforts.

“Nearly all of the shoreline in the Chesapeake Bay is privately owned, so decisions about shoreline management are happening with individual property owners,” said Bilkovic. “By assigning an economic dollar value, you can at least insert those ecosystem benefits into the cost-benefit calculation. Right now, they're not there.”

Living shorelines provide many other ecological benefits that can be associated with economic impact. Like hardened or armored shorelines, they mitigate erosion from waves and storm surges. However, they also filter out unwanted nutrients from runoff and trap sediment, serving as an important carbon sink.

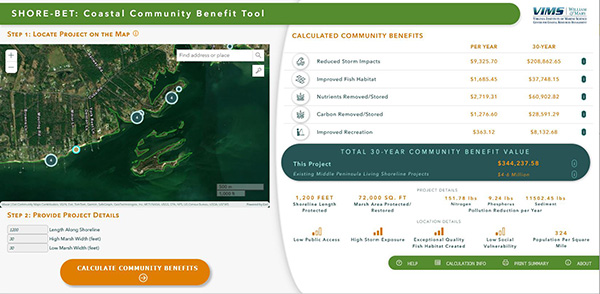

Moving forward, the researchers are working to create a shoreline restoration benefit calculator called SHORE-BET. It attempts to capture important economic and societal benefits provided by marshes and living shorelines for coastal communities.

Moving forward, the researchers are working to create a shoreline restoration benefit calculator called SHORE-BET. It attempts to capture important economic and societal benefits provided by marshes and living shorelines for coastal communities.

"Fisheries are one important component, but we are working to estimate values for many of the other services such as carbon sequestration, flooding risk reduction and nutrient removal,” said Scheld. “The better we can account for these ecosystem services, the more informed coastal communities can be when making decisions impacting their environment, economy and overall quality of life.”

The full manuscript of the study is available online at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964569124001352