VIMS researchers monitor “red tides” in local waters

Researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science continue to monitor the algal blooms that have been discoloring local waters during the last few weeks. These “red tides” occur in Chesapeake Bay every summer, with their onset, distribution, and longevity controlled by water temperature, nutrient levels, and other factors.

Red tides are caused by dense blooms of microscopic algae that often contain a reddish pigment. Algae are normal components of all aquatic environments, but some species produce toxins and can generate what is known as a “harmful algal bloom” or “HAB” when they occur in significant numbers. HABs can harm both marine organisms and human health.

VIMS professor Kimberly Reece first reported the bloom that is now visible in the lower York River on August 8th. This is several weeks later than the York River bloom appeared last year, likely due to this summer’s cooler temperatures.

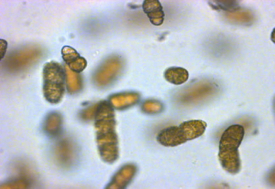

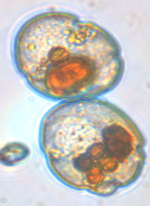

Reece notes that the York River bloom is currently composed mostly of Cochlodinium polykrikoides—a species of algae that has bloomed in the area for decades—but also includes low numbers of Alexandrium monilatum, a relative newcomer. Reece and fellow VIMS professor Wolfgang Vogelbein, her colleague in HAB research, report a denser bloom of A. monilatum in the North River off of Mobjack Bay, and a bloom of a third species called Gyrodinium instriatum in White's Creek near the mouth of the East River.

Reece notes that the York River bloom is currently composed mostly of Cochlodinium polykrikoides—a species of algae that has bloomed in the area for decades—but also includes low numbers of Alexandrium monilatum, a relative newcomer. Reece and fellow VIMS professor Wolfgang Vogelbein, her colleague in HAB research, report a denser bloom of A. monilatum in the North River off of Mobjack Bay, and a bloom of a third species called Gyrodinium instriatum in White's Creek near the mouth of the East River.

There is currently no direct evidence of harm from the recent blooms. Reece says “Blooms of Cochlodinium, Alexandrium, and closely related species may harm oyster larvae and other marine life, and have been found associated with fish kills, but we’ve had no reports of any of these effects in local waters this year. A. monilatum has been associated in past years with the death of some experimental animals in seawater tanks at VIMS, but that has not happened this year.”

Reece says a fish kill was recently reported in White's Creek—with hundreds of dead small menhaden—but cautions that “we don't want to assume that the event was directly linked to the Gyrodinium bloom. The fish had been dead for quite a while, so it could have been from any number of causes, including a fish dump.” Fish and crab kills can also be caused by low levels of dissolved oxygen, which are associated with blooms of many different species and occur when the algal cells die, sink, and decay.

Reece and Vogelbein, members of Virginia’s Harmful Algal Bloom Task Force, partner with other colleagues at VIMS, and representatives from the Virginia Department of Health, the Marine Resources Commission, the Department of Environmental Quality, and Old Dominion University to track the appearance of algal blooms within Virginia waters and to determine whether the bloom organisms pose any threat to marine life or human health.

Anyone who has observed a patch of water that is colored red or mahogany and is concerned should contact Virginia's toll-free Harmful Algal Bloom hotline at (888) 238-6154.

Algal Blooms in Perspective

Algal blooms are not uncommon in lower Chesapeake Bay during the spring and summer. Algae respond to the same conditions that encourage plant growth on land, and thus are most likely to form blooms when waters are warm and nutrient rich. Excess nutrients from farms and yards, sewage treatment plants, and the burning of fossil fuels are one of the biggest challenges facing the Bay.

“There are three main ingredients for an algal bloom,” explains Reece. “Warm waters that favor rapid growth of algal cells, abundant nutrients to fertilize that growth, and wind and tidal currents that allow the cells to form dense aggregations.”

Sampling & Monitoring

Real-time monitoring of algal blooms is not an easy task, as it involves microscopic analysis combined with developing and applying DNA tests to rapidly identify the potentially harmful algal species from among a huge variety of mostly benign microorganisms. Development of these molecular DNA assays is a primary focus of Reece’s research at VIMS.

Real-time monitoring of algal blooms is not an easy task, as it involves microscopic analysis combined with developing and applying DNA tests to rapidly identify the potentially harmful algal species from among a huge variety of mostly benign microorganisms. Development of these molecular DNA assays is a primary focus of Reece’s research at VIMS.

Monitoring also requires daily collection of water samples from all across lower Chesapeake Bay. Analysis of these samples shows that Cochlodinium is currently blooming in the York, James, Elizabeth, and Lafayette rivers; and near where the East and North Rivers empty into Mobjack Bay.