Researchers show that three fish families are one

Research by an international team of scientists including Asst. Professor Tracey Sutton of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science has resolved a long-standing biological puzzle by showing that a group of deep-sea fishes previously classified into three separate families are actually the larvae, males, and females of a single family—the whalefishes.

To put the team’s discovery into perspective, consider that cats, dogs, and walruses also represent three biological families. It’s as if the researchers discovered that dogs are really male walruses, and that kittens aren’t cats but a walrus’s juvenile form.

Their findings, published in the January 22 issue of Biology Letters, represent “the most extreme example of metamorphoses and sexual dimorphism ever documented in vertebrates.”

Sutton attributes the long-standing confusion over the classification of these fishes to their rarity and to the difficulties of deep-sea sampling. Because the adult forms of these fishes typically live between 3,000 and 12,000 feet below the surface, they are rarely collected in sampling nets. The few that are netted are typically in poor condition by the time they are brought aboard a research vessel.

Sutton says that museum collections around the world contain only a few hundred female specimens, and fewer than 10 males. “Prior to this study, there was not a single undamaged male specimen in any museum anywhere,” says Sutton.

Specimens of larvae are more common, as these migrate into shallower waters to feed, but they differ so markedly from their adult forms that scientists had never previously recognized their family kinship.

“The males, females, and larvae are so radically different that no one ever suspected they were related,” says Sutton. The fishes had been incorrectly classified for more than 50 years.

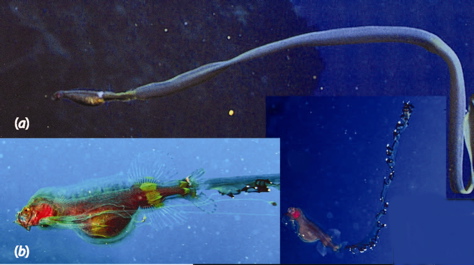

Larvae are almost all tail, with a small, upturned mouth designed for eating tiny shrimplike creatures called copepods. Females have huge mouths with long, horizontal jaws that allow them to capture larger prey. Males cease feeding, lose their stomach and esophagus, and apparently convert the energy derived from feasting on copepods as larvae into a massive liver that supports them throughout adult life.

Sutton describes the males as “swimming noses and testes.” “They have enormous nasal organs, and they spend their adult lives searching for a female before their liver fails.”

"There’s got to be a joke in there somewhere,” he laughs.

Scientists first began to suspect a connection between these markedly dissimilar forms during a broad Japanese study of fish genetics, which showed that deep-sea larvae traditionally classified as tapetails were genetically similar to adult female whalefishes.

Sutton helped place another puzzle piece when he collected a juvenile female whalefish off Africa in 2007 that was just starting to transform into an adult. “The specimen was beginning to lose its pelvic fins, which made a light bulb go off in my head,” says Sutton. Adult whalefishes lack these fins.

Sutton says that when he sent a picture of this larva to co-author John Paxton of the Australian Museum in Sydney, Paxton “nearly keeled over.” Sutton says that Paxton, whom he calls the “whalefish guru,” immediately realized that the specimen was a ‘missing link’ between tapetails (larvae), bignose fishes (males) and whalefishes (females).

Careful sampling by Sutton in the Gulf of Mexico had previously turned up several intact male specimens that he sent to co-author G. David Johnson of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Johnson’s careful scrutiny of the bone structure of these and other males provided additional evidence of their relation to female whalefishes.

Other co-authors of the study include the Japanese scientists who led the genetic component of the research: Takashi P. Satoh and Mutsumi Nishida of the Ocean Research Institute at the University of Tokyo; and Tetsuya Sado and Masaki Miya of the Natural History Museum and Institute in Chiba, Japan.