VIMS prof honored by Inventors Hall of Fame

Method for producing spawnless oyster has revolutionized aquaculture

Professor Stan Allen of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science joined exalted company in late October when he received an Inventor of the Year Award from the New Jersey Inventors Hall of Fame, whose inaugural class includes Thomas Edison and Albert Einstein.

Allen, who directs the Aquaculture Genetics and Breeding Technology Center (ABC) at VIMS, was honored with colleague Ximing Guo for their “product by process” patent for oysters with two extra sets of chromosomes. The pair accomplished their breakthrough in 1994 while at Rutgers University, where Guo continues to work. Allen arrived at VIMS in 1997 as ABC’s first director.

Allen and Guo’s invention—plus subsequent enhancements at VIMS and Rutgers—has revolutionized oyster aquaculture worldwide, including its recent rapid growth in lower Chesapeake Bay. More than 90 per cent of Virginia’s farmed oysters result from the production method they created. The ABC hatchery at VIMS currently operates the most extensive breeding program for oysters in the U.S., and arguably the largest in the world.

Allen and Guo’s invention—plus subsequent enhancements at VIMS and Rutgers—has revolutionized oyster aquaculture worldwide, including its recent rapid growth in lower Chesapeake Bay. More than 90 per cent of Virginia’s farmed oysters result from the production method they created. The ABC hatchery at VIMS currently operates the most extensive breeding program for oysters in the U.S., and arguably the largest in the world.

Allen was “pleasantly surprised” by the award. “It just came out of the blue,” he says. “It’s nice to be acknowledged in a larger setting than the oyster world.”

VIMS Dean and Director John Wells says the award attests to the hard work and creativity of the Institute’s faculty. “To paraphrase one of Stan’s Hall of Fame colleagues, invention requires both inspiration and perspiration. This award speaks to both parts of that equation for Stan, who continues to work nonstop on innovative efforts to advance oyster aquaculture in the Bay and around the world.”

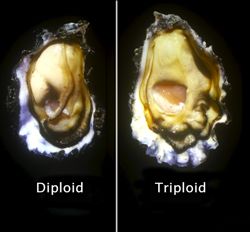

Allen and Guo’s oysters are called “tetraploids” because they contain four chromosomes in each cell nucleus rather than the pair of chromosomes found in regular “diploid” oysters. Breeding tetraploids with diploids in turn creates “triploid” oysters, whose three sets of chromosomes renders them incapable of reproduction. The same general process is used to create seedless fruit.

Because triploid oysters devote no energy to reproduction, they grow to market size more quickly than fertile oysters, produce more meat, and can be harvested during summertime when spawning-associated decreases in meat quality normally puts the harvest of wild oysters off limits.

The rapid growth of triploid oysters is particularly important in Chesapeake Bay, where a pair of oyster diseases—MSX and Dermo—has devastated wild stocks. Because of their faster growth, triploid oysters reach market size in about 18 months, 6 to 12 months before their wild brethren and importantly before the usual age of disease-associated mortality. The triploids have also been found to be more tolerant to the two diseases, for reasons still unknown.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Allen and his colleagues in ABC’s oyster hatchery at VIMS continue to conduct basic and applied research on all aspects of oyster biology and domestication, including studies of the process by which tetraploids are produced and selection for even better disease tolerance in the triploid oysters that now dominate aquaculture in Virginia.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Allen and his colleagues in ABC’s oyster hatchery at VIMS continue to conduct basic and applied research on all aspects of oyster biology and domestication, including studies of the process by which tetraploids are produced and selection for even better disease tolerance in the triploid oysters that now dominate aquaculture in Virginia.

“These research questions have real implications for the Virginia industry, especially hatcheries,” says Allen. The ultimate idea, he adds, “is to give growers the aquatic equivalent of a seed catalog from which they can choose an appropriate variety to custom fit their particular farming operation.”

Those operations continue to grow, with the latest figures from VIMS’ annual report on the economics of shellfish aquaculture showing a 20% increase between 2011 and 2012 in the number of farmed oysters sold by Virginia growers—from 23.3 to 28.1 million—with 2012 sales valued at $9.5 million. Total direct employment associated with sales of farmed oysters in 2012 reached 70 full-time and 106 part-time jobs in the Commonwealth.