Survey reflects rapid expansion of Virginia’s oyster aquaculture

Virginia’s oyster hatcheries saw a more than 18-fold increase in the number of seed and larvae sold between 2007 and 2008, according to a survey of shellfish farmers conducted by researchers from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science's Sea Grant Extension Program. The survey also found that hatcheries are predicting an additional four-fold increase in sales in 2009.

“This impressive growth is almost entirely due to sales of eyed oyster larvae to growers using remote-setting techniques,” says Tom Murray, VIMS Marine Business Specialist and Director of Virginia Sea Grant’s Marine Extension Program.

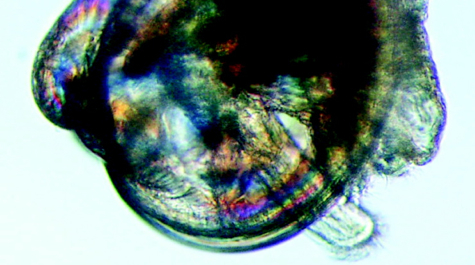

Remote setting, also called spat-on-shell, is a method of oyster cultivation that involves allowing larvae to settle and metamorphose on old oyster shells in land-based tanks. The shells with attached spat are then planted directly on the bottom, without cages or other structures. This allows for more economical production of clumped oysters that are suitable for shucking. Virginia hatcheries began selling oyster larvae in 2008, as spat-on-shell methods caught on, and more than 498 million larvae and seed were sold. Projected hatchery sales for 2009 come to 1.66 billion.

Oyster aquaculture, based on improved culture techniques and disease-resistant oyster seed, is replacing Chesapeake Bay’s traditional oyster fishery, which has declined significantly in recent years, primarily as a result of endemic oyster diseases and increasing wildlife predation of seed oysters.

Murray and Aquaculture Specialist Mike Oesterling have been surveying Virginia clam and oyster farmers annually beginning with the 2004 crop year. The 2008 crop survey documents a small decline in clam plantings and sales but continued growth in oyster aquaculture. More than 185 million farmed clams—worth $27.3 million—were sold by Virginia growers last year—down 13 percent from an estimated 2007 sale of 212 million clams. About 9.8 million farmed oysters went to market in 2008—up from 4.8 million in 2007, and surpassing the industry prediction of 7.3 million.

“The sale of farmed oysters by Virginia growers has increased ten-fold since our initial survey covering the 2004 crop,” says Oesterling. “In previous years, hatchery production of seed seemed to be a limiting factor in the growth of our oyster aquaculture industry, but the data suggest that hatcheries are ramping up production to meet the demand for seed and larvae.”

The study notes overall growth in employment in shellfish aquaculture while indicating the difficulty in estimating actual employment numbers for what are still relatively small oyster culture operations.

The complete report can be downloaded at http://web.vims.edu/adv/aqua/MMR2009_5.pdf