Hard Clams

Hard Clam Broodstock Evaluation (Mercenaria mercenaria)

The first resident director of VIMS ESL, Michael Castagna, and his staff researched the spawning and larval history of a wide variety of bivalve species and most notably conducted the research and development of methods for aquaculture of the hard clam Mercenaria mercenaria in the 1960s and ‘70s (https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports/1263/). As a result of his work, Virginia now has the largest hard clam industry in the nation. The bulk of Virginia’s hard clam aquaculture is based on the Eastern Shore, primarily in the lower Chesapeake Bay and in coastal bays on the seaside of the peninsula, where ambient conditions provide higher salinities. Hard clams are typically less tolerant of low salinity environments, limiting the expansion of the hard clam industry in the estuary. These salinity limitations often manifest during low salinity episodes rather than average conditions, such as the heavy rainfall of 2018. That year, heavy precipitation in the Chesapeake Bay’s watershed resulted in 15 ppt salinity reaching all the way to the mouth of the Bay, which heavily impacted shellfish hatcheries and growers in the region.

In support of Virginia’s hard clam industry, VIMS ESL established wild sourced broodstock clams collected from four high salinity locations along the U.S. East Coast: Cape Cod, MA, Great Bay, NJ, Wachapreague, VA, Bogue Sound, NC and two lower salinity sites in Chesapeake Bay: Mobjack Bay and Pocomoke Sound, VA. These clams represent the genetic diversity of hard clams within their natural range and have been used to investigate physiological tolerances of the species and to develop molecular tools for breeding and tracking genetic diversity within clam production lines.

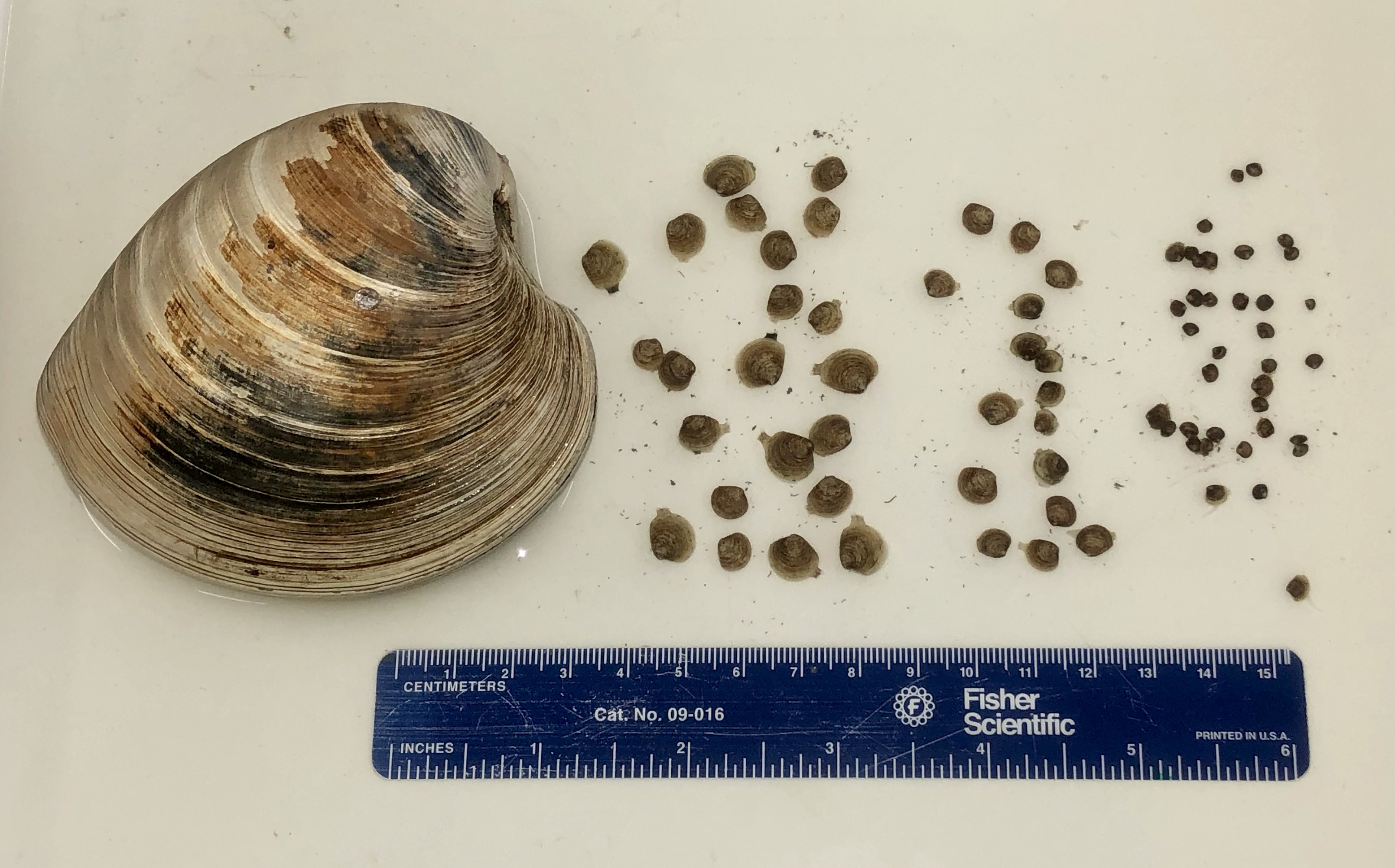

Independent clam stocks and strategic crosses have been spawned and maintained separately. All resulting progeny were cultured in ESL’s hatchery and nursery through the larval and early juvenile stages. Thermal and salinity tolerance tests were conducted on larvae and juveniles from each line to determine physiological tolerances of each group or cross. When clam seed reached a size large enough to be retained by grow-out gear, the clams were moved from the nursery to the field where they were placed in mesh bags retained within bottomless cages. This allowed the bag to settle down into the sandy bottom, where the clams could bury in the sediment while still being retained within the bag for easy retrieval or assessment. Once the clams outgrew the mesh bags, they could be planted directly within the bottomless cage. Animals and gear were maintained regularly and survival and growth were monitored throughout development. To test grow out performance at a commercial scale, ESL also provided clam seed from lines and crosses to commercial growers on Virginia’s seaside and in the Chesapeake Bay, with lower and more variable salinities.

This work has been supported by Virginia Sea Grant and the Virginia Agriculture Council.