VIMS professor merges science and art

Science and art are often considered opposite ends of a broad spectrum, but are they really so different?

Wolfgang Vogelbein, a professor at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, has built a life on the parallels he draws between science and art—and his life-long search for the truth that lies within each discipline.

“For me, the ultimate goal in scientific research and art has always been about finding the truth,” he says. “Both involve problem solving and using creativity and innovation to reach a masterpiece, which takes a culmination of years of experimentation.”

A pathologist in charge of the VIMS Electron Microscopy and Histopathology labs by day and wood-turner by night, Vogelbein has become accustomed to juggling his two passions. With more than 25 years at VIMS, Vogelbein’s scientific goal is to understand the causal links between environmental change (pollution, climate change, eutrophication) and disease in Chesapeake Bay fishes. His artistic goal is to create custom wooden pieces in his garage-turned-studio.

Vogelbein’s research focuses on evaluating how exposure to chemical contaminants called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons affects the development of cancers in wild fishes. He’s particularly interested in pancreatic and vascular cancers within a population of mummichogs that inhabit a creosote-contaminated Superfund site in the Elizabeth River.

Vogelbein has spent hours on-end peering through the lens of a microscope, studying every detail within these and other cancerous tumors. He says that it’s paradoxically the most aggressive and nasty tumors that are visually the most beautiful—both in fish and trees.

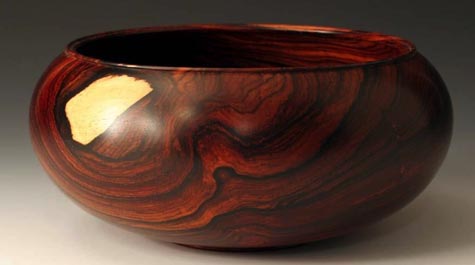

Tree burls—which are actually tumors—are the Holy Grail for wood-turners. Vogelbein constantly keeps his eyes peeled for trees with burls along their trunks. “A burl is a proliferation of tree sprouts and buds, and every wood-turner is always on the lookout for them,” he says. “The designs found inside a burl are wild and beautiful, just like the inside of a tumor found in a fish.”

Vogelbein has acquired many burls throughout his career as a wood-turner, and has his own philosophy on procuring the wood needed to create his artwork. “Wood is locally abundant, diverse, and for the most part free,” he says. “The majority of my pieces are made from local, rescued wood that I’ve obtained from commercial loggers, downed trees from storms, or from commercial and residential development. In fact, many of my pieces have come from trees that have fallen on the VIMS campus.”

Obtaining wood is only the first step in a surprisingly lengthy process, says Vogelbein. From chopping, to sealing, rough turning, air drying, sanding, and finishing, wood-turning a single piece can take months if not a year or more. The patience needed to see a long-term project from start to finish is another area where Vogelbein sees parallels between art and science.

Vogelbein’s art—which he marketed as Sarah’s End Woodcrafts—used to fly off the shelves at Cristallo Art and Glass Studio in Williamsburg, until the gallery owners decided to close their doors to focus on their own artwork. “When I was selling my artwork at Cristallo’s, I was really burning the candle at both ends,” he says. “I would come to work at VIMS all day and then I’d be in my shop turning wood until about 3 a.m. I’m happy to be back to doing it just for the love of the craft.”

Vogelbein says the pieces that speak to him the most all help portray the human condition. “When working with wood, some pieces depict the flaws of age, while others portray the impeccability of youth,” he says. “As an artist, you evolve over the years and get to a point where you can express yourself and say something that has some sort of meaning.”

In addition to his study of liver cancer in mummichogs, Vogelbein is investigating a bacterial infection that affects Chesapeake Bay striped bass, with the ultimate goal of understanding how the disease might impact the striped bass stock. Recently, Vogelbein and his colleagues found evidence of disease-associated mortality that is now being used to better manage the stock, and built a fish disease challenge laboratory at VIMS to investigate which environmental factors have modulated the emergence of this chronic bacterial disease. Vogelbein also collaborates closely with VIMS Professor Kimberly Reece on the health impacts of harmful algal bloom species, including a recently emerging one called Alexandrium monilatum.

“There are so many parallels between my research and artwork,” he says. “I’m just crazed about both of them.”

Vogelbein says that what drove him to become a scientist and an artist was his curiosity about the beauty and workings of the natural world. “The key factors in being both a scientist and an artist are passion, persistence, and hard work,” he says.

“Science and art are oftentimes considered as completely different entities, but they aren’t,” says Vogelbein. “Science and art is all about experimentation. If you were to go back in time, even the most famous artists would have basements and attics full of failed experiments. Making, inventing, discovering, and creating are all methods of problem solving.”