MA project may jumpstart market for offshore wind energy

The pending approval of a major wind farm off the southern coast of Massachusetts will send a "market signal" that is likely to jumpstart development of other wind farms in the nation's coastal waters, including those off Virginia.

That's according to Charles Natale, Jr., President and CEO of ESS Group, Inc. ESS is the lead environmental and engineering firm for Cape Wind—the first offshore wind energy project in the continental U.S. Natale is a 1982 graduate of the College of William and Mary's School of Marine Science at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

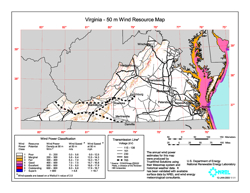

Wind-resource maps produced by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) show that Chesapeake Bay and Virginia's offshore waters provide ample opportunities for generating wind energy. Nearly all of these areas exceed the NREL threshold for "utility-scale" wind-power development.

Natale described the Cape Wind Project and his firm's role in its on-going design and permitting process during VIMS After Hours Lecture for September. The lecture drew more than 100 people to the VIMS campus in Gloucester Point.

Natale expects that the Interior Department's Minerals Management Service—the project's lead federal agency—may give the final go-ahead for the project before the end of the year. He says this "record of decision" is likely to be appealed, but thinks the project "will prevail in the appeal for all the right reasons." He expects erection of turbines to begin in 2011.

Proposed in 2001 for Nantucket Sound off the southern coast of Massachusetts, the Cape Wind Project is designed to use 130 wind turbines to produce up to 468 megawatts (MW) of electricity, enough to power about 160,000 homes.

That compares to 1,500 MW of rated capacity for the coal-fired power plant recently proposed for Surry County in Virginia, and 500-1,300 MW for modern nuclear facilities.

Each Cape Wind turbine would rise 440 feet from water to blade tip, in water depths of 12 to 50 feet, with another 80 feet of foundation pile sunk into the seafloor. The turbines would occupy an area of approximately 24 square miles whose boundaries range from 5 to 10 miles offshore. A network of submarine cables would collect and move the wind-generated energy to the onshore power grid.

Wind power is emissions-free, renewable, and domestically produced, but that is not to say that the Cape Wind project has sailed through the regulatory process unhindered.

The scope and location of Cape Wind have made environmental assessment of the project a monumental task—and provide a "test case" that Natale hopes will facilitate and streamline future environmental assessment of offshore wind farms elsewhere in the U.S.

"The scientific studies and evaluations required for Cape Wind were pioneering in many respects," says Natale.

Because the turbines would occupy the seafloor, water column, "water sheet," and atmosphere, Cape Wind's environmental studies required close cooperation among a wide variety of agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, , the U.S. Coast Guard, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Federal Aviation Administration, among several others.

The location of the project, seaward of the 3-mile state-federal maritime boundary, adds additional regulatory complexities. Decisions concerning siting and operation rest with a federal agency—the Minerals Management Service. But to do any good, the turbines' electricity must be brought ashore via submarine cables that cross state-managed waters, and then enter into a welter of local, state, and regional jurisdictions.

Natale believes that the experience gained in navigating the nation's first-ever environmental assessment for offshore wind will combine with recent federal incentives to soon make the financial risks of wind power attractive to investors.

"Design and construction of offshore wind farms pose significant up-front costs," says Natale. "The initial cost estimate for Cape Wind was $750 million, back in 2001. It's now about $1.7 billion—copper, petroleum, steel, everything has gone up. That all affects the return-on-investment."

Without market incentives, investors see little reason to fund wind farms. In today's market, utilities can produce electricity using traditional fossil fuels—such as coal—at about 4 cents per kilowatt-hour. Electricity from wind currently costs more than three times as much—around 15 cents per kWh.

Tax credits, grants, loan guarantees, and other incentives help reduce the gap. The 2008 Congress extended the investment tax credit for renewable energy for 8 years, until 2016, and the production tax credit for 1 year.

"Investment tax credits help wind-farm developers defray their significant up-front costs," says Natale. "A few years ago investors would have to take the risk of capital up front to get a project in the ground, and then get tax credits after it started producing. Now they get tax credits when they invest. That's brought a lot of capital to the table."

Once a wind farm is built, its advantages are clear—production of energy that is free, renewable, domestically produced, and emissions-free. "The best thing about wind energy is not only clean air, but no fuel costs over the long run," says Natale.

He believes these advantages, plus the increasing cost of fossil fuels, will soon turn the tide for wind-power development.

"Cape Wind will be the market signal," says Natale. "A lot of large utilities and investors are very interested in wind, and they all say ‘When Cape Wind gets these turbines in the ground, we're in.' Once Cape Wind is in play, I think you will see quite a bit of pick-up in the offshore wind-energy market. It all makes sense."

Natale stresses the importance of the environmental assessment process in addressing and minimizing concerns raised by environmental groups and citizens during the Cape Wind project.

For instance, ESS spent 3 years and almost $3 million to study potential impacts on bird populations in Nantucket Sound. Their findings, confirmed by the Massachusetts Audubon Society, show that the turbines would have minimal impacts on seasonal or migratory birds.

"We estimate that the average mortality would be 2 birds, per turbine, per year," says Natale. "On a relative scale, the mortality rate was very low."

Another major concern with wind farms is the visual impact of turbines rising along the horizon. "Visual-impact assessments are the single most controversial issue with these projects," says Natale. To assess these concerns, ESS produced visual simulations to show how the turbines would appear from the shoreline.

"If you're standing on shore and you hold up your thumb, you'd see the first digit of your thumb in terms of scale," says Natale. "The difficulty is that it's a value judgment. I might think the turbines are beautiful and majestic, you might think they're ugly. This was a very contentious and dynamic debate, and a debate that was well worth having."

Wind Power in Virginia?

Wind-resource maps produced by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) show that Chesapeake Bay and Virginia's offshore waters provide ample opportunities for generating wind energy. NREL ranks wind power in 7 classes: Class 1, with average winds below 12.5 mph, ranks as "poor." Class 7, with average winds above 19.7 mph, ranks as "superb." Nearly all of Chesapeake Bay ranks above Class 4, which is typically taken as the threshold for "utility-scale" wind-power development. All of Virginia's offshore waters also rank above this economic threshold.

Several factors favor offshore wind development over land-based wind farms. For one, the water surface provides less friction than land, making for stronger winds. Also important is that offshore wind farms can be placed near the heavily populated coastal areas that need the energy. Energy generated on the windy plains of the nation's midsection must be transmitted long distances to reach market, reducing efficiency and adding extra costs for transmission towers.